Why a Homelab?

Public cloud platforms allow us to build, scale, and operate applications with great ease and at a relatively low cost. And not just in pure infrastructure terms. Our time is also a very important cost, and creating these infrastructures, acquiring hardware, preparing data centers, setting up networks, and so on involves very high costs in terms of time, effort, and infrastructure—costs that cloud platforms help us avoid.

At first glance, everything seems like a win. However, in practice, our own organizations and their bureaucracy, cost controls, essential security constraints and policies, and even connectivity issues often limit our agility when consuming cloud environments. GitHub published a revealing figure in 2024: their repositories contain more than 39 million exposed secrets. Without going any further, 84 out of every 10,000 commits include AWS keys. Finally, two out of three organizations use Kubernetes—it is a de facto industry standard due to its countless advantages.

Given this context, having cloud/Kubernetes-based development environments is increasingly necessary. But as we see in our day-to-day work, operationally this comes with certain frictions, especially when sharing specific contexts across development and infrastructure teams. This prevents us from being more agile when testing ideas and/or leads us to duplicate infrastructure—and therefore resources. And what if you’re a student? Budget constraints are even tighter, and credits for running complex labs run out quickly.

A homelab changes this context. It allows you to replicate the topology of a real Kubernetes cluster (control plane, nodes, networking, storage) in a physical and secure environment, without relying on hourly billing or the risk of exposing keys or endpoints, impacting third parties, or sharing contexts. Can we do the same on our local machine with kind or minikube? Yes—but not quite. We need much more power, and the cluster will compete with our local resources without physical isolation.

What if we want a homelab with dedicated hardware? The use of mini PCs and Raspberry Pis is becoming increasingly common. They provide great flexibility at a very low cost. In many cases, Raspberry Pis start to pile up, as they’re not only used for homelabs but also become part of the home setup: Pi-hole, home automation, and more.

What Is Turing Pi?

This is where we arrive at Turing Pi, a board that allows you to group multiple Raspberry Pi modules, NVIDIA Jetson modules, and in its latest version, its own custom hardware modules, to form a small, compact, efficient bare-metal Kubernetes cluster with very low power consumption.

At its core, it turns low-power hardware into a highly available bare-metal platform capable of running containers, Kubernetes, or any Linux-based workload. Let’s take a quick look at its components:

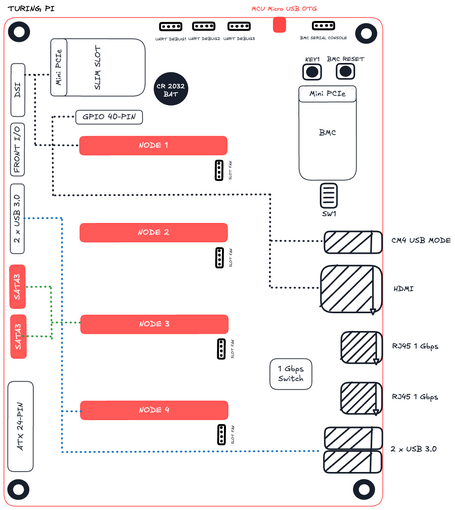

Turing Pi 2 board:

The Turing Pi 2, its latest version, can host up to four CM4 modules, each acting as an independent node. In addition, it includes:

- BMC (Baseboard Management Controller) to monitor, power on, and power off each node remotely.

- Two SATA ports to connect SSD or HDD drives.

- mPCIe and SIM slots, designed for 4G/5G or NVMe modules.

- Internal and external Gigabit Ethernet connectivity.

- ATX or PicoPSU power supply and standard Mini-ITX form factor, compatible with ITX cases such as the Streacom DA6.

- On the rear side, there is also a microSD slot, in addition to those included on each CM4 module adapter.

Let’s look at the component compatibility matrix depending on the type of module:

| Vendor | Model | mPCIe | M2 (NVMe) | SATA | USB 3 | USB 2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turing | RK1 | ✔️ | ✔️ (PCIe 3.0 x4) | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| Raspberry Pi | CM4 | ✔️ | ❌ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| Nvidia Jetson | Orin NX Orin Nano Xavier NX TX2 NX |

✔️ | ✔️ (PCIe 4.0 x4) ✔️ (PCIe 3.0 x4) ✔️ (PCIe 4.0 x4) ✔️ (PCIe 3.0 x2) |

✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| Nvidia Jetson | Nano (B01) | ❌ | ✔️ (PCIe 2.0 x1) | ❌ | ❌ | ✔️ |

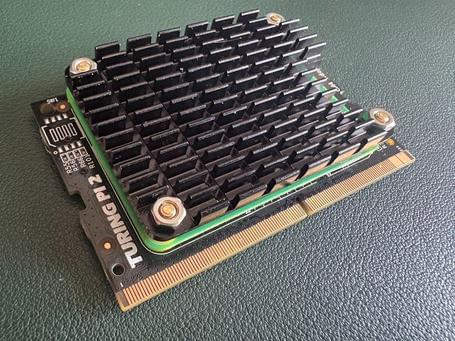

CM4 module with adapter and heatsink:

Each node in the cluster can run an ARM64 Linux-based operating system. The usual choice is Raspberry Pi OS Lite (formerly Raspbian), since we don’t need a graphical interface. On top of that, a lightweight Kubernetes orchestrator is installed, with K3s being the most common option due to its low footprint and simple deployment. The control plane is typically hosted on module 1, which acts as the master node, while the remaining modules serve as workers, forming the data plane. This setup faithfully reproduces the architecture of a cloud-based Kubernetes cluster, but in a compact format.

It’s also worth noting that the board itself includes a BMC (Baseboard Management Controller)—an independent chip that acts as the board’s “auxiliary brain.” This controller (based on an ASPEED AST2500, the same one used in many enterprise servers such as QNAP or Dell EMC) allows you to power on, power off, or reboot each node remotely, monitor temperatures, control fans, and update firmware without needing to connect a keyboard or display.

The BMC runs a customized version of OpenBMC, accessible via SSH or a web interface, and has its own dedicated Ethernet connection. From it, you can flash CM4 modules, install operating systems, monitor cluster health, or automate tasks via IPMI or Redfish—just like in a real data center environment. In practice, it turns a set of Raspberry Pis into a fully manageable mini data center, tangibly reproducing the management layer we usually take for granted in the cloud.

While the Turing Pi 2 provides a real distributed environment, its raw performance is not overwhelming. Jeff Geerling, one of the leading figures in the Raspberry Pi community, has shown that a full cluster with four CM4 modules does not match the performance of a MacBook M1. However, its energy efficiency is outstanding: each module consumes between 2 and 7 W, meaning a full cluster rarely exceeds 30 W in total. This performance-to-power ratio makes it an ideal platform for learning, orchestration testing, and 24x7 continuous deployment, without the noise or electricity cost of a conventional server.

In upcoming chapters, we’ll see how to assemble our Turing Pi and how to install Kubernetes and its nodes. But instead of using K3s as suggested by Turing Pi, we’ll make things more interesting by turning to Talos—a more efficient and, above all, declarative way to start getting real value from our homelab. Because understanding physical infrastructure is the first step toward designing and architecting better solutions in the cloud.

Comments are moderated and will only be visible if they add to the discussion in a constructive way. If you disagree with a point, please, be polite.

Tell us what you think.