CSS has come a long way from its days of purely static styling: today, it not only defines how a website looks, but also how it adapts, thanks to tools like media queries, custom properties, and @supports. Now, something new is peeking through that could take things even further: the if() function.

Yes, you read that right: conditionals directly within CSS properties, without needing to write a single @media, repeat rules, or duplicate styles. It's a way to bring a bit of conditional logic from other languages into stylesheets. It's not magic (even if it seems like it); it's the future of CSS, and it’s already begun.

This article explores, with visual and practical examples, how the if() proposal in CSS works. Although it’s not widely supported just yet, its syntax is already fully defined and it’s shaping up to be a key tool for the next era of frontend development.

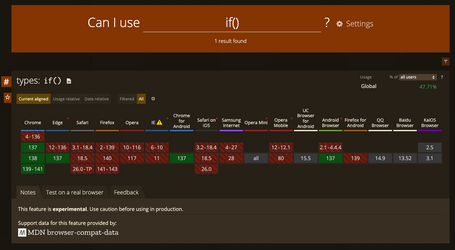

✏️Note: if you want to test any of this, make sure your browser is up to date. It's currently available only in Chrome 137 or later and Edge 137.

Definition explained

If CSS could think, it would probably use if(). This function is still in draft status at the W3C. Since the evolution of CSS began, if() has been a long-standing request, and the fact that Chrome now supports it means it’s likely here to stay. It promises to bring conditionals directly into our CSS rules.

The structure is simple and looks something like this:

div {

color: if(

style(<some-condition>): <some-value>;

style(<some-other-condition>): <some-other-value>;

else: <default-value>;

);

}

What it does is evaluate an inline condition and apply one value or another depending on the result. No more repeating blocks with @media, @supports, or inventing weird hacks. Pure CSS logic.

Until now, these logics were handled by combining @media, variables, additional classes, or directly with JavaScript. With if(), we can have much cleaner, more portable, and declarative styles.

Style conditionals

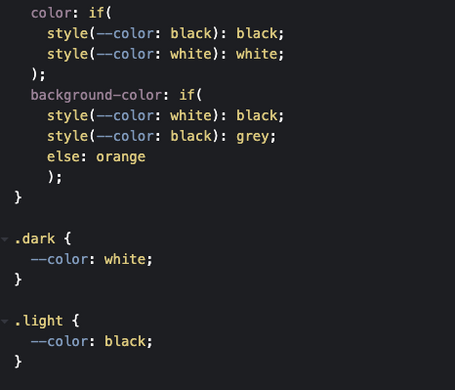

Style conditionals evaluate the value of a custom CSS variable to make visual decisions. Perfect for themes, states, user settings, or even props in web components.

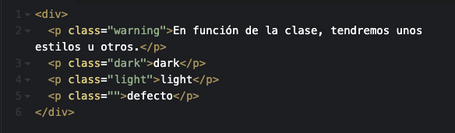

Example: light or dark theme

Got a --color variable that defines if the mode is light or dark? With if() you can change the color automatically!

Let's define a simple HTML file, a couple of paragraphs with "light" and "dark" classes.

Sure, you can also do this with classes and variables. But what's interesting here is the if() function—we’ll complicate things later. I’m declaring a style based on a variable and applying that value if it exists.

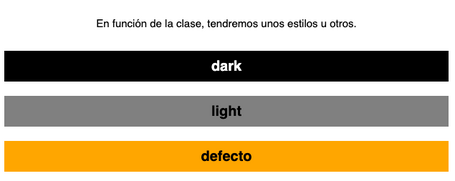

This gives us the following:

The result? A theme that responds automatically without toggling classes, using JavaScript, or writing 20 extra lines. And if --color isn’t defined, the default color is used.

(To those wondering why the default color is orange… what’s wrong with orange?)

Tip: Ideal for design systems and component frameworks where you want each piece to behave independently based on variables.

Media conditionals

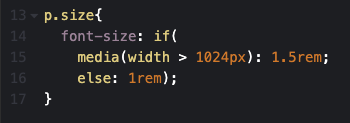

Using if(media(...)) lets us apply different styles based on the environment: screen width, orientation, device type, etc… It’s the responsive CSS of the future.

We all know @media since we’ve used it over and over again for responsive design. You've probably resized your browser window just to see how the layout adjusts. Not much explanation needed: the result is familiar.

Example: text size based on width

No big surprises here. If the width exceeds 1024px, the font size is 1.5rem. If not, it stays at 1rem. The power here is that you no longer need to duplicate rules or break the natural flow of the component.

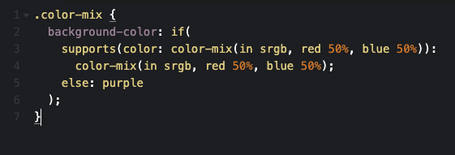

Feature support conditionals

With this, we can finally say goodbye to vendor prefixes and one of the biggest headaches we face: that one browser only your client uses...

Yes, @supports isn’t new, but if() does it more directly. If it’s not supported, it skips the content. Plus, you can still define a default behavior.

Example: color mixing with color-mix

Let’s apply a background color using color-mix, if supported. If not, we’ll just set a fallback color. This avoids writing separate fallback rules.

Pro tip: You can use supports(...) inside if() for any property: fonts, filters, shadows, etc.

A slightly more complex example

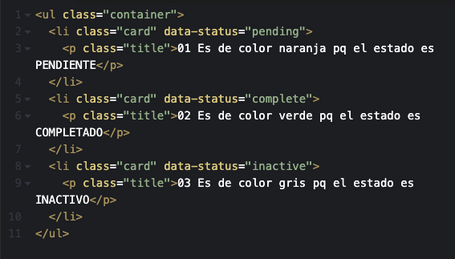

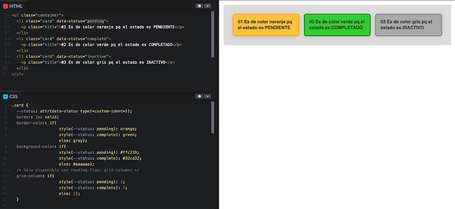

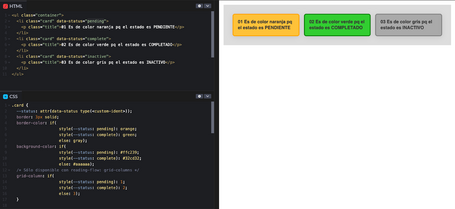

Let’s apply this new conditional approach to modify the appearance and position of some cards. Think of a mini Kanban board where cards change style based on their state.

We start with three cards. They share the class card and all have a data-status (if not, they default to "inactive") with values like pending, complete, or inactive.

We’ll skip unrelated styles like body, container, or card…

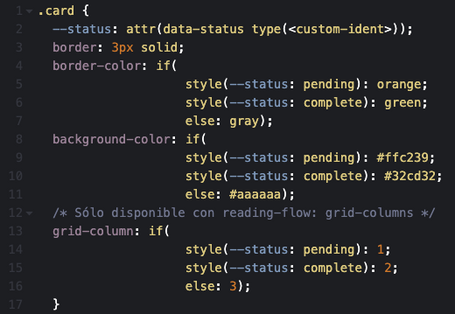

By creating the --status variable, we can read each data-status in our HTML via attr().

We use type(

if(style(--status: ...): compares the value of --status and applies different styles for each case.

Being able to define different states directly inside each property is a major declarative shift. It might feel odd at first, but with structure it’s very clear.

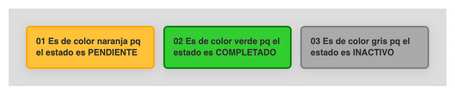

In the end, this --status variable defines the border color, background color, and grid column, giving us something like:

This allows changing the data-status in the HTML (e.g., from the backend) to instantly change visual styles. For instance, when all tasks are completed, your HTML could look like this:

This approach completely decouples HTML from CSS. Just by changing data-status, you can modify multiple visual styles without touching any CSS or adding more classes.

Conclusion

Beyond how cool it sounds, the if() function gives us:

- Declarative, easy-to-read styles

- Modular, reusable CSS, perfect for design systems and components

- More dynamism without JavaScript

- Less repetition: fewer @media, fewer @supports, fewer utility classes

In short: more power, less clutter.

Although if() in CSS is still being implemented (and we don’t know exactly when it will land), its potential is clear. It brings us closer to a smarter, more compact CSS that's more aligned with design logic. We're no longer just applying styles—we're making decisions within our CSS rules to apply them more efficiently.

Even if you can’t use it just yet, designing with this mindset can help structure your code better today.

Comments are moderated and will only be visible if they add to the discussion in a constructive way. If you disagree with a point, please, be polite.

Tell us what you think.